Website under construction

Please check for updates

Booked lecturing (plse check as these update regularly):

- QV518 Cunard 2025

- QV602 Cunard 2026

The Turin Shroud - A CSI Review

Very recent application of the latest technology throws new light on the age, source of the images and story of the potential victim captured in the shroud held in Turin

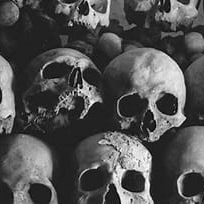

Our lives write themselves into our bones; what we eat, where we live, our family history, illnesses and injury, diet and idiosyncrasies, children birthed or lost, they all provide the human story to the skeletal framework holding us together in life and subsequently.

As members of the Homo Sapiens club we may have the same physiology. But we are different to each other perhaps by minute variations in measurements of length or depth of bone, in overall height, hair, skin and eye colour. These differences make up who we are.

Kate Schroder MBE FRSA

Biography

Dual Honours Degrees at Sheffield University, 1987, in both Human Archaeology and Prehistory, majoring in forensic recovery in the field and the human behavioural aspects of Early Man. Field work undertaken includes excavation of a large burial site.

Facial Reconstruction certificate, Sheffield University, 2020. Crime scene management, Human remains dating and recovery, COVID-19 management, Carbon dating techniques, and multiple other certificates gained 2019-2023.

Researched for PhD at Buckingham University, linking to Cranfield University in 2022 - Evidence for surgery and enhancing clinical outcomes, 2020-2023. Published in University Press and in mutiple university texts in UK and Australia, 1998 onwards subjects including raising the alarm in healthcare settings. Text available upon request. Consultee to Private Members Bill Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998. Researched for PhD in Law and Ethics at Middlesex University Business School.

25 year + career in UK healthcare sector including NHS, working as a CEO and a professional interim transformation and improvement director. Awarded MBE for services to health in 2012, CIPFA and Cabinet Office Public Sector Turnaround award, Third Sector and Kings Fund Innovation awards x 3.

Lecturer and guest speaker globally since 2015.

CEO of Queen Alexandra Hospital and End of Life Care unit for Military Veterans, working under the banner of Care for Veterans till late 2024. MD of Royal Hospital Chesterfield Foundation Trust's wholly owned subsidiary servicing Derbyshire NHS Hospitals and repoorting on the 'state of the nation' Primary Care, in 2024/25.

Podcasts arriving shortly

Facial Reconstruction

Bringing people back to life

Using both clay and software, skulls can be built upon using established methods incorporating the 52 Manchester points for tissue depth; the smallest variations in skulls at any of these markers results in a unique face distinguishable from others

Access podcasts shortly

What sets us apart

We look and behave differently now and in previous groupings of the Homo species

Tracking our past

From the first day our earliest ancestors began to walk upright, carry their young long distances, our journey began. It was not a linear pathway. Many subspecies lived at the same time and often in the same places. So far, at least 15 different subspecies came before Homo Sapiens. All evidence is that we may not have been the strongest or the smartest rather that we learned to adapt to changes in climate and to live in larger social groups, creating the stratified society we recognise today.

Identifying the source of current traits

We are a product of previous species - DNA mixed to create unique facets of physique and behaviour that power our ability to both thrive and develop. Most non-African DNA includes up to 5% Neanderthal and in some isolated areas of the world, more than 5% can be identified.

In West Africa, a ghost DNA has been identified in at least three geographic locations including Yoruba and Ebo. Other areas of the world are bound to host similar mysteries about who lived before the genus hosting Homo Erectus or Homo Sapiens.

We are still unravelling our past and as technology opens up new avenues of research, our story wil become even more complex.

The same techniques are used to solve crime as to unravel the mysteries of our distant past

Reconstructing faces from the past uses the same techniques regardless of the age or circumstances of the bones.

A choreography exists for the moments leading up to death having criminal or tragic accidental factors. Changes to tissue can leave marks upon bone, occupation, ethnicity, general health and any survived illnesses or injury, surgical procedures, or causes of demise may also show on bone

Lectures

Constantly updating and developing new themes

- Becoming Human – Man’s rise from stone axe to computers

- The Neanderthals inside us all – most of us carry up to 5% Neanderthal genes today, and what that means about how we look, act and live

- Gibraltar -the final years of Neanderthals, why was Gibraltar special enough to protect Neanderthals from what caused their demise elsewhere

- War and Peace – Love and War between the four species of early man who walked the earth at the same time

- Out of Africa- Early Man’s life, struggles to survive and thrive from 2.4m years ago

- Australia – Early Man’s expression of life through rock art and bone

- Making Faces from the Past – demonstrating facial reconstruction to bring people back to life from 2m year ago, from Egyptian times to present day to solve criminal cold cases, and in modern surgical techniques following accident or illness

- The Real CSI – the range of techniques used to solve complex crimes and some real-life examples

- Archaeology in Crime Solving – the application of modern archaeological techniques used to solve some of the most well-known and heinous crimes

- Surviving in Nelson’s Navy – an introduction to the most successful surgeons in Nelson’s navy, how they worked including how they saved Nelson three times but lost him once. What life was like on board for the sailors.

- The Crew of the Mary Rose – a reconstruction of the day the Mary Rose sank taking most aboard with her, how they lived and what they looked like.

- Unwrapping Mummies – a look inside unwrapped mummies using CT scanners to reconstruct what they looked like and how they lived

- Pompeii – Inside the Volcanic Casts – using CT scanners to look inside the volcanics casts of people who perished during the eruption of Vesuvius. Reconstructing how they looked, lived and died. A walk through the city as it was.

- Cooking 1m year ago to present day – the evidence for cooking and diet from before Man learned to use fire through to present day and the range of food available as far back as 2m years ago.

- The Real Pirates of the Caribbean – Who they were, what they looked and lived like and how they became pirates.

- The 20 Most Fierce Pirates in the World – a countdown globally over the last 400 years to present day. The men and women who ruled the seas.

- The Vikings – who they were, how they lived, what they looked like.

- Viking York – how the city was built within a Viking stronghold and what remains today of people, cultures, behaviour and buildings.

- Viking Dublin – how the city was formed, by whom, how people lived and what they looked like.

- The Magic of Stonehenge – who built Stonehenge and why. What was its purpose? Alat, disco or hospital?

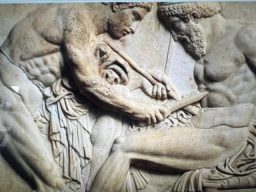

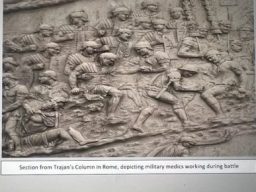

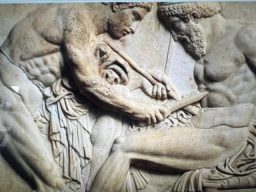

- Roman Medicine and Surgery – the surgeons, their equipment, how they operated and what we do today that the Romans devised.

- Women in Medicine – the role of women in medicine including during the world wars and how they changed the way people survived before women were allowed to practice.

- The Top Ten Medical Innovations – a count down to the most important breakthroughs in medicine and how they affect us today

- Underneath London – the evidence for how Londoners lived through 2000 years, taking in Romans, the Black Death and the world wars.

- The Mummies of Peru – what the Peruvian peoples looked like, how they lived, and who the mummies were/ how they were selected as chosen people.

- The Medicinal Garden – the role of medicinal gardens through thousands of years including many examples of plants and their uses in the past and for the future.

- The Murder Gene - How was it that Homo Sapiens replaced all other sub species who lived at the same time. Do we carry a murder gene?

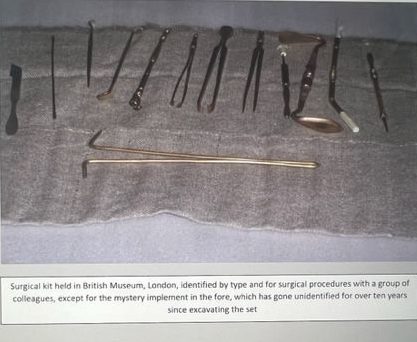

Evidence for Surgery in Roman Britian

Available in full publication

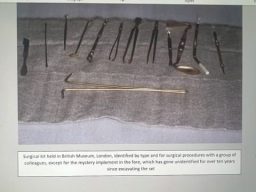

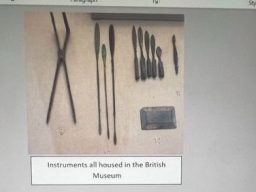

The original aim of this research was to present the evidence for surgery and medicine in Roman Britain as fully as possible. This would have meant listing all known equipment, inscriptions, buildings and skeletal evidence ‘thought’ to be related to this subject. The work undertaken makes some distinction between material finds and their full interpretation. has now been recognised as being a feat beyond that possible of lesser mortals, given both the consistent unearthing of new finds and the often, dubious links between finds and their full meaning. For instance, equipment having a possible surgical use may also have a more innocuous purpose; many small implements are now thought to have been used to apply cosmetics or during grooming. Ear wax scoops may have been used to take ointment from a pot. The potential for error when determining use of an artefact is huge.

Problems of classification and interpretation have shown to be as much of a deterrent to the aim of the research- to be accurate and factual - as the time available to it. As excavations are constantly unearthing new finds, so the size of task of cataloguing them grows. At some stage every researcher has to decide upon a time to stop and write up. I picked mine and so this research might be subsequently overtaken. I welcome that opportunity to read what others identify and interpret.

During research and writing, a process of selection has to be incorporated. What do we incorporate and what do we set aside? It goes without saying that the direction of this work and its end- product may differ from work undertaken by someone else under the same circumstances. Their opinions and backgrounds may be different to mine. This is a factor over which I have had no control, but in order that these differences were kept to a minimum several ‘rules’ were devised before researching and writing began.

Wherever possible, comparisons between modern and Roman surgical implements have been undertaken by the people who use them in a modern setting and on a daily basis. Whilst ideological and cultural norms may be greatly different for the two periods, Roman and modern, the objective assessment of implements having a possible surgical use is more or less unaffected by time. The Romans undertook routine gynaecological examinations, for instance, and the implements used would had had little or no use with male patients, or with women having non-gynaecological ailments. They look incredibly like modern equipment sued for the same purpose and in fact, surgical tools used in the USA up to the 1850s were identical by type, design, and use.

Medical equipment included in this edition has also been identified using literary sources from the same period, and by comparison with tools of the same period which are known to have come from the kits of certain doctors, (tombs) or which have been depicted on the tombstone of doctors.

Skeletal evidence used has been restricted to that showing signs of direct surgical intervention, applying an understanding as to the level of skill being necessary from each set of human remains where survival and any positive clinical recovery would not have been otherwise possible.

Evidence used in this edition as an indication for military hospitals and healing centres of a religious nature used by both military and civilians, has been restricted to examples having a continental counterpart for which documentary evidence and/or evidence obtained from contemporaneous literary sources, exists.

Evidence for practising oculists and pharmacists has been obtained from the presence of ointment stamps and containers which list the contents and often the name of the practitioner. The use of the contents is also good evidence as to the aims of the people involved. We are able to draw sound conclusions as to the skill of these medics and the catchment area for their products, (and probably the types of ailments experienced at this time.) We know from detailed writings of the period that cataract surgery was commonplace during the Roman period, and that ophthalmic surgeries were held across the Roman world including Britain.

In summary, by cross referencing finds in Roman Britain with both a modern context and with finds identified across the rest of the Roman world, an objective view has been taken about the degree and type of surgical activity taking place across Roman Britain.

Available shortly

Improving Clinical Outcomes - Research including Postmortem Reviews

Investigating previously misunderstood or missed evidence for surgery and medicine - Available via publication in early 2024

This research considers the ways in which medical knowledge and allied practical resources were deployed across Roman Britain. It is proposed that a decision to treat was made upon the indigenous population of Britain during the period forming that of the Roman occupation i.e. 43 – 410 AD, according to location and perceived socio economic value of the patient. Location appears to be associated with availability of local medical resources as well as the location of trade links, road networks and relationships between indigenous population and Roman occupier. It is also proposed that this selection process and the circumstances resulting in the availability of resources in Roman Britain, is echoed in modern times where a population is being subdued by an occupying force. For this reason, the lessons learned from Roman Britain may be translated into planning and strategies associated with modern warfare and even with considerations about the deployment of peace keeping forces across the globe.

This research asks if the ways in which gender, age, potential value as a working commodity and the variances represented by geographical localities, all impacted upon treatment delivered – both the outcome of a decision to treat and the availability of necessary skills and resources.

One outcome of the treatment decision was the impact upon relationships between Roman and British peoples – the occupying force and the indigenous peoples. Conversely, the relationships further added to the decision to treat. Where relationships were more difficult, resources were located at distance in more friendly and therefore safer and more developed or more defendable locations. Tensions also made the decision to treat less likely. Just as today, emergency services are aware of potential patients, buildings, and areas that are inhospitable even to the degree that police escort is requested prior to attendance by ambulance, paramedic or fire service. In Roman Britain, without modern digital communications, and given the state of occupation, the request for a medic to enter difficult locations was likely to go unanswered.

There are also modern parallels relating to the rejection of medical support being offered by an occupying force; it is not only a case of being unwilling to accept help but also a matter of differences of faith, medical knowledge, and the acceptance of the tools and the procedures themselves. The established belief is that the Romans brought with them a step change in medical skills, equipment and surgical procedures and that the Iron Age was a period of dire risk of poor clinical outcomes from illness or injury. This research challenges that view and asks whether Iron Age medical practices were both skilled and sustained during Roman occupation.

It is important to ask where Iron Age medical practices continued into the Roman era in Britain, too, and to identify what was special about those locations. Was there an association with locations experiencing tension with the occupying forces; did the location of Roman military, trade or travel related resources play a role in determining who was treated and who was not. .

Another factor is that, for the indigenous population, faith was closely linked to health and treatment. Faith tends to represent a variable in decisions about treatment. Roman medical resources, when given, were more consistently applied even by type of surgical procedure. Training for medics was more about process than beliefs. This is especially true following the establishment by Augustus of a hierarchy of military medical training, practices and supervision.

Even in Roman Britain there is evidence of skilled Iron Age surgery in pockets located according to several factors including the nature of relationships with the Romans. This research will lay them bare. Similarly, there are clearly evidenced Roman surgical procedure ‘factories’ with marks upon the skeletal remains that almost allow one to identify that one medic delivered many procedures to multiple patients, in one location. Just as today, surgeons concentrating on one form of procedure become expert in it to the degree that they are far faster, and the clinical benefits to the patient far more positive in terms of quality or recovery and survival, than their peers. Roman Britain became a powerhouse for ophthalmology, for instance, with several sources of reliable evidence signposting that Roman medics delivered more cataract revisions in Britain than elsewhere in the Roman world.

It is proposed here that the evidence signposting how sustained Iron Age i.e. non- Roman medical treatment was far more commonplace in geographic areas of tension. It is also proposed that as a consequence, the decision to treat was weighted against the occupied population where relationships were poor, the location of expert Roman medical resources was at distance, and the socio-economic value of the patient low. Roman medics were simply not about to risk themselves in order to travel long distance into unfriendly territory, in order to attend a non-Roman patient, regardless of their ranking within their own tribe. The decision to attend or to stand down would not have been a personal one rather tone taken by Roman military leadership.

Commander Simon Thompson, NHS Consultant Psychiatrist and qualified medical doctor having rank in both Airforce and Army as well as service during active tours of duty abroad, explains the decision-making around provision of medical support from an occupying force; ”It is largely about the balance of risk and duty. Military medics are a valuable commodity, being highly experienced and trained to give medical aid to their colleagues. Losing one of them would have a catastrophic effect upon the troops especially should they be located away from central command and the opportunity for replacement. Military medics are fully employed within their own troops. There would be little time to spend on travel to treat civilians and any decision from command to undertake such a task would require an armed escort, further depleting resources. The circumstances affecting a decision would be the same regardless of the time period, modern or historic” (Squadron Leader Dr. Simon Thompson, January 2020).

Troops in Roman Britain were stretched and under pressure to achieve and to maintain, control. Operating at the limit of the Roman – held global territory and with pressures from elsewhere, resources were not limitless. Military activity, medical and otherwise, would have been closely managed by their leadership.

The background to these hypotheses is that a comprehensive understanding of medicine and surgery in Roman Britain has been constructed over several decades using four main types of evidence – written, artefactual, skeletal and architectural.

This range of evidence has formed the basis of established belief about the nature of medicine and surgery in Roman Britain. Established belief is that the occupation mobilised a strategically-formed medical resource consistently across Roman Britain drawing upon the models associated with the framework developed by Augustus i.e. through the legions and their established trained medical troops, known throughout the Roman Empire as medicus, and largely utilising battlefield triage techniques combined with static military facilities and hospitals. The traditional view is that background health and nutrition improved under Roman rule. This research questions that view, using methodologies to determine risk of mortality and nutritional or physical health, to refresh the review of skeletal remains found in Britain from both Iron Age and Roman periods.

However, despite the volume and range of evidence taken into the framework of traditional understanding, some of it seemingly anecdotal, there are still gaps in the record that have been filled by extrapolating from what is recorded elsewhere in the Roman world. There are also issues relating to the quality of material creating the archaeological record for instance the recording of grooming artefacts as medical equipment. More recent literature has explored these elements and they are addressed within the chapter on Literature Review.

This research:

- Strips back the traditional record relating to medicine and surgery in Roman Britain, including written, artefactual, architectural and skeletal material, in order to reach a baseline comprised of robust material having no erroneous or misleading elements for instance equipment that may have been used for grooming rather than for surgery;

- Fills visible gaps in the record using new evidence filtered against a robust criteria and without applying variable or unsound adjustments;

- Adds further substance to the quality of evidence used so that a refreshed understanding may be reached about who was treated, who by, how, where and why (or why not).

This exercise will also provide answers to the currently unanswered question as to who was not treated, and why not. The scope of this factor is likely to include location in terms of accessibility and nearness to available resources, relationships between Roman occupiers and the indigenous peoples, and the localised beliefs embedded at the time of the occupation for which significant new evidence is emerging to indicate that Roman beliefs and behaviours did not consistently replace Iron Age aspects. This research throws light upon why that might be, in this case the Roman response to illness or injury when sustained by non-Roman patients, and the location of necessary resources.

Literature excerpts and full publications loading here shortly

A full set of lectures including those showing hands on facial reconstruction wil be available here shortly.

July 2023

Share your finds

Remember both privacy and copyright best practice

Treat finds that may be human as if they were land mines - don't dig them up, avoid sicking anything in the ground next to finds as this risks destroying foresnsics and stratigraphy. Take a photo on your mobile phone if you have one handy so that the context - the location of the find- can be identified, and report to the authorities. They will keep you updated on what the find is, within the limits of legal constraints.

More pictures loading shortly

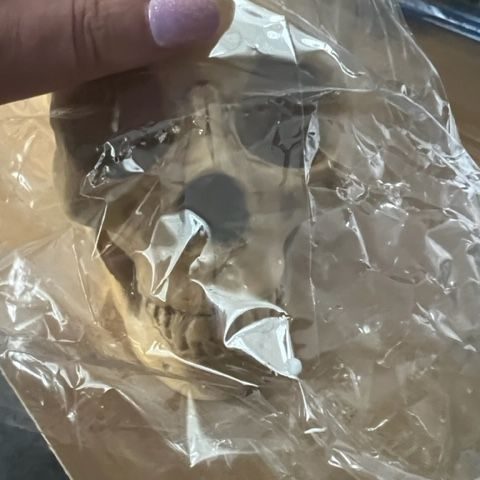

New skull cast arrives

Opening up the package

Many ladies are please to receive chocs or flowers; not I. The skull cast is wel protected during transit and warpped in see through plastic to further protect it whilst it is being made ready for assessment and reconstruction.

Further posts to follow

We need your consent to load the translations

We use a third-party service to translate the website content that may collect data about your activity. Please review the details in the privacy policy and accept the service to view the translations.